The following is Part II in a multi-part series on how to draft and leverage an ESI protocol in any litigation. Part I of our series discussed the When, How and Why in planning for and creating your ESI protocol. In conjunction with this series, eDiscovery Assistant has created a new section in Checklists and Forms titled ESI Protocols that will include new content with each part of this series.

The most important part of crafting an ESI protocol is to make sure it fits your case. Much like a protective order and/or scheduling order require you to consider the individual needs of a matter, drafting an appropriate ESI protocol requires considering what the collection, review and production of ESI will look like for your case. You need to anticipate issues and plan for them. Some questions to ask before drafting a protocol include:

- What are the sources of ESI that you anticipate being at issue? Be specific — email, attachments, mobile devices for text messages, photos, etc., instant messaging platforms, social media, source code, etc.

- Where are the sources and what has to be done to collect them

- Are the sources all within your custody or control?

- Will you have third parties that have data relevant to the case?

- What technology do you have to handle data? Will you handle data internally or hire an outside provider or discovery counsel?

- What are the data issues specific to each source of ESI you have identified? i.e. what format will data be provided in, what metadata fields do you need, etc.

- Are mobile devices at issue and how will those be captured? Different methods have different implications.

Generally, drafting an ESI protocol should come AFTER you have conducted custodian interviews and have answers to these questions so you know what needs to be included for your case.

So what are the components of an ESI Protocol?

- Governing Rules and Limited Applicability. Start your protocol with a statement on the rules that govern the case. Include the federal or state rules and the local rules. It’s important to define what governs the order in the event of a dispute, and not all states mirror the FRCP. This section should also limit the order to the captioned action and state it does not apply to future litigation.

- Cooperation. A short statement indicating that the parties agree to act in good faith and cooperate consistent with the Court’s guidelines. This is important when the court you are in has a specific requirement articulated for cooperation, but it really should be included all the time. And you should cooperate.

- Proportionality. A simple sentence that the parties agree that the ESI provided will be proportional to the needs of the case. While proportionality can be used as a weapon to narrow discovery (particularly in plaintiffs class action matters), courts want to see that the parties know and understand proportionality and will live within its bounds. Note that the revised FRCP incorporate the Rule 26 statements on proportionality into each one of the discovery rules.

- Liaison. Several courts now require that each side appoint a liaison for ediscovery issues, meet and confers, etc. This section should identify those liaisons for the court. This is optional unless required by the court.

- Definitions. I’ve drafted protocols that may or may not include this section, and my preference is to include them. Should you have motion practice and need to discuss specifics, having these terms defined in the order will assist you in getting that information before the judge. Definitions may include: ESI, native file, metadata, load file, static images, OCR, producing party, receiving party, discovery material, etc. Most judges won’t understand them, but the technical folks handling the data will, and you should start to learn them.

- Process for identification of Custodians, Exchange of Information and/or ESI Disclosures. This is optional but can be beneficial if one side suddenly asserts you should have provided data from additional custodians or additional data sources down the line (and that happens a lot). The process simply states if the parties agree on a number of custodians (include how many), when that information will be exchanged, what information will be provided about each custodian, whether parties can request additional custodians (yes, on a good faith basis with some justification from data or deposition testimony), and how it should be done. For data sources, it provides a timeframe for parties to exchange information on the data sources for custodians and non-custodial sources (think email systems, databases, etc.)

- Scope of Preservation/Preservation Obligations. Whether to include this section depends on several factors that are unique to each case. The model order for the Northern District of California includes a list of sources that are considered inaccessible that the parties do not have to produce, but frankly, that list is very outdated with the technological advancements that have been made, and it often results in fights about whether the receiving party should get those categories of information. The concept of inaccessibility is much narrower now than when that form was drafted. That being said, if you want to limit data sources that will not be searched or produced, this is the section to do it in. This section can also include a date range for preservation that defines the scope of what will be searched.

- Search/Use of Technology Assisted Review (TAR). I’m including these together here, but you’ll likely want to split them out if you are negotiating a TAR protocol. If the parties are proposing search terms, setting out a process for how those terms will be determined, how they will be applied, whether search term reports will be provided to the opposing party and the process for negotiating terms should be set out. Similarly, if the parties are agreeing on using TAR, that protocol will be its own section or even a stand alone order on how that will be conducted. Note that Rule 34 does not require the parties to exchange search terms or agree what technology can be used to satisfy a party’s obligations under the FRCP.

- Production Format/Form of Production. This is the most complex part of the protocol and one that we’ll cover in detail in subsequent parts of our series here. I’ve seen this area handled different ways in protocols, and my preference is to include all of the details about the production format in one section of the protocol. That includes: native v. TIFF and specifications for images, metadata fields to be provided, extracted text, if native files will be provided for what types of documents, whether and how placeholders will be provided, applying bates numbers, de-duplication (global vs. other options), de-NISTing, email threading, maintaining families, what is in color vs. black and white, labeling for confidentiality in compliance with protective order, whether signatures will be separated out as attachments, and redaction. Depending on the complexity of the case, redaction may be a subsection that needs to denote the categories for redaction and the specific wording to be used for redacted material, as well as how metadata fields will be populated to allow the receiving party to know what documents were redacted, and whether native redaction tools can be used during review. Keep in mind that you’ll want to have separate paragraphs to deal with unique issues for sources of ESI. If you have source code, instant messaging, text messages, etc., you want to spell out how those must be produced. I also like to include that the parties will notify each other of technical difficulties with received productions.

- Manner of Production. This is a separate category that many overlook. Although FRCP 34 provides that documents can be produced 1) in the ordinary course of business or 2) in response to requests, we rarely get either with ESI. Information produced by source, by custodian or with the native file path as a metadata field helps identify the source. However you request data be provided, you are stuck with Rule 34 unless you get agreement from the other side. Manner also includes physically sending the productions — whether by STFP (secured file transfer protocol like Sharefile or Egnyte), encrypted hard drive, etc. Note too whether the parties will send a cover letter or email to identify the production.

- Sampling. In certain situations, conducting a sampling of data to determine the value of potential relevant information comes up. If you foresee that in your case, you’ll want to include a catch all paragraph that states that if sampling is required, the parties will meet and confer on a process for identifying the data to be sampled, how results will be provided, and if possible, the measure of whether the results indicate the identified relevant data is proportional to the burden to get it and what cost-shifting may be available.

- Phasing. In complex cases, it may make sense to agree to a phased approach for discovery. Phasing can include specific custodians, sources or categories of data or date ranges of data. The parties can agree on a phased approach that the court signs off on and allows them to point back to later as necessary. This language can be very helpful if data produced at the end of discovery opens up a new avenue that needs to be explored and you need a basis for asking for more time to explore that limited topic. Courts are more inclined to provide time when it is focused and has a basis for the request vs. that you just didn’t get discovery done in time because you dragged your feet.

- FRE 502(d) or No Inadvertent Waiver. We’ll cover this very important topic in detail in another post in our series. There are competing arguments as to whether to include this section in the ESI protocol vs. having a stand alone order. If you use the same language in the protocol and set it out as a separate section header, I see no reason not to include it, but it’s a matter of personal preference. Both are orders by the court once signed. FRE 502(d) precludes waiver of privilege for inadvertent production of privileged or protected materials, IF the parties agree to a 502(d) order. You can find language for this section on our sample ESI protocols and sample 502(d) order.

- Privilege Log. The FRCP set out the requirements for a privilege log and many local court rules add additional information on timing for producing a log (contemporaneous with production vs. at the close of discovery). It’s a good idea to incorporate those rules or state how a log will be generated (electronically using metadata is common), how you’ll deal with email threads on a log (separate entry for each one or one for the thread), what, if any, additional fields you want added to the log and the process for disputing entries on the privilege log.

- Modification of the Order. Generally, include a paragraph that this order can be modified by the parties or the court for good cause shown and what to call the subsequent order so the court and the parties track which order is currently in play.

- Signature Block. This order should be signed by the parties and submitted to the court for signature with the appropriate certification of service.

The list above is a broad brush for what to include. While there are many, many specific details that I could add, an ESI protocol just needs to fit your case. If you’re unsure about technical specifications, consult with your provider or discovery counsel to review them. There is no one way to organize a protocol, but some components make sense to group together for readability, and having those first three sections here up front signal to the judge that you know and understand that proportionality and cooperation are key and the parties are on that road. Form of production and the pieces that go into that for specific types of documents are best grouped together so the technical folks know what to follow.

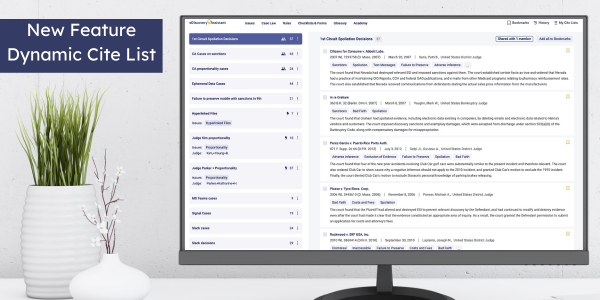

This is a long list, and one that I’m sure seems overwhelming. I’ve included many pieces that won’t be at issue in smaller cases, but you need to know what you are deciding to leave out. Take it one piece at a time and consider the value for your case. Build a template for your cases that you can work from that includes just what you need. You can refer back to our checklist on the Components of an ESI Protocol and use the sample orders provided in eDiscovery Assistant as a starting point. We advise against taking those sample orders carte blanche and using them — they have to be adapted for your specific jurisdiction and case.

We’ll be providing more in depth analysis on various pieces of a protocol in our continued posts in this series. In Part III of the series, we will discuss the top ten situations you can avoid with a protocol.